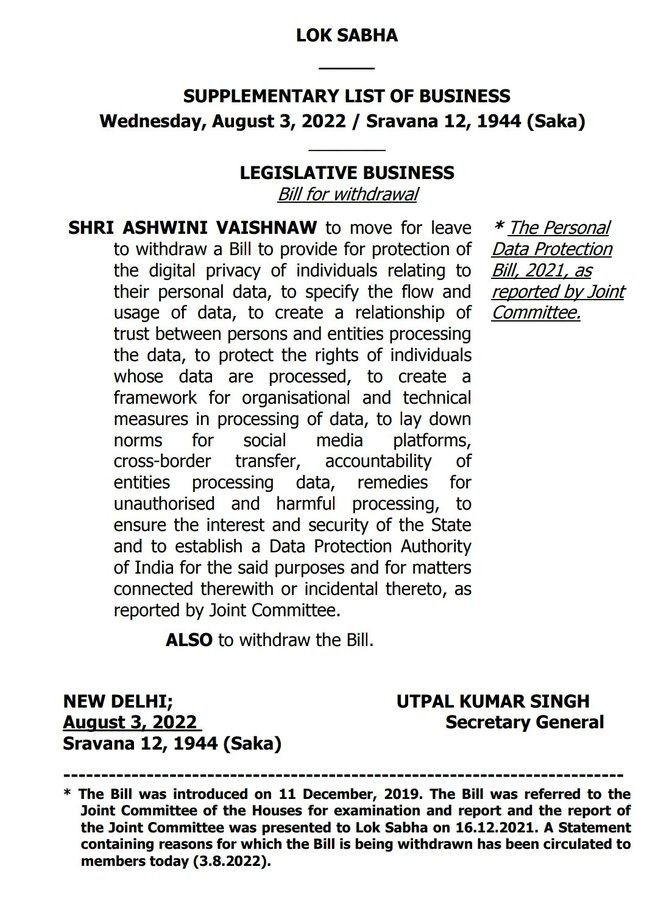

With the withdrawal of the PDPB 2019, some parts of the industry feel relieved, some are feeling Déjà vu. Some feel that the dreaded law will never come back.

It is no doubt a disappointment and loss of momentum for those who were looking ahead to India being in the global community of nations, more than 130 of which have data protection laws in one form or the other. The EU personal data vendors will now look down on India as a lost hub for data processing and prefer to move over to Phillipines or other countries where cost efficiencies and other advantages compete with India.

While we hope that the Government may come up with an alternate draft soon, the professionals in the industry should note that there is no vacuum as far as the data protection law is concerned in India.

The PDPB 2019 was expected to repeal Section 43A of ITA 2000 which was directly comparable to PDPB 2019. Now that PDPB 2019 is no longer there, Section 43A will be more relevant as the “Data Protection Law of India”.

Additionally we need to note that Courts are continuing to recognize principles of Data Protection as was envisaged in the PDPB 2019 or those referred to in the international regulations like the GDPR and pronouncing judicial orders related to “Right to Forget” and other privacy principles which have been discussed in the body of the Puttaswamy judgement though they were not part of the final judgement in the Puttaswamy case.

For example, a recent ruling in the Karnataka High Court (WP12596/2022) an order has been issued to provide interim protection related to a “Right to Forget” application by a few respondents who were earlier acquitted in a certain case. We have seen similar orders earlier from high courts of Odisha, Madras and Delhi. These orders mean that judiciary already recognizes the provisions of PDPB 2019 and other data protection laws as operative under the Puttaswamy judgement. More appropriately these are considered “Due Diligence” and part of the “Reasonable Security Practice” under Section 43A and Section 79 of ITA 2000 as amended in 2008 with notification of rules in April 2011.

Hence Section 43A of ITA 2000 qualifies to be called the current Data Protection law of India.

The enforcement agency under ITA 2000 are

a) CERT IN in respect of Data Breach Notifications and contravention of Section 70B

b) Adjudicator in respect of claim of any damages by any person for contravention of any of the provisions of the Act

c) Police for prosecution of any criminal offences under Chapter XI of the ITA 2000

Obviously, these regulatory agencies are not as powerful as the envisaged data protection authority of India (DPAI) under PDPB 2019 nor has the focus on Privacy and Data Protection like what the DPAI was expected to do.

Generally the penal provisions under ITA 2000 and invoking the power of the Adjudicator under Section 43A is accepted only when a victim who has suffered a damage approaches the authority.

However, the rules of 2003 on Adjudication provides powers to the Adjudicator for “Suo Moto” action. Hence when there is a need any of the Adjudicators (One in each state) can take action against any person who caused damage to any other person even if the victim has not approached the Adjudicator (IT Secretary of the State or UT).

The Adjudicator can impose fines and either make payment to the identified victims or hold it in trust for them and ask them to make the claim. He can also invoke criminal investigation as may be necessary.

Similarly, the CERT IN is the agency to which any data breach has to be reported within 6 hours. CERT IN also can invoke adjudication or prosecution as it may deem fit.

Thus Between the three law enforcement agencies namely, the CERT IN, Adjudicator and the Police, both civil and criminal proceedings can be initiated under ITA 2000 for any contravention of Section 43A and/or other sections.

Organizations can thank themselves that the Adjudicators and CERT IN Director General at present have not shown any inclination for suo moto action. But the law does not bar them from realizing their powers and a sense of duty that may prompt them to take action as would a DPAI would take. In the event of non compliance not leading to a data breach, authorities may not impose a penalty but a disciplinary fine may still be a possibility.

Having therefore taking note of the presence of a “Trinity of Regulators” for Data Protection in India, we can now focus on the details of Section 43A compliance. While looking at Section 43A compliance we may note that 43A is just one section that can be invoked under ITA 2000 when there is any contravention of law related to “Sensitive personal information”. This does not mean that the law does not address “Non Sensitive personal information” or “Non Personal Information”. ITA 2000 addresses both Personal and Non Personal Information and both Sensitive personal information and Non Sensitive personal information.

Non sensitive personal information is covered under Section 72A as a criminal offence as well as Section 43 as a Civil wrong. When Section 43 is invoked,, Section 66 also becomes relevant and can impose 3 years of imprisonment to a person who causes a data related loss. The criminal offences extend to individuals through the operation of Section 85.

Additionally Section 67C speaks of data retention, Section 69,69A,69B are related to disclosures.

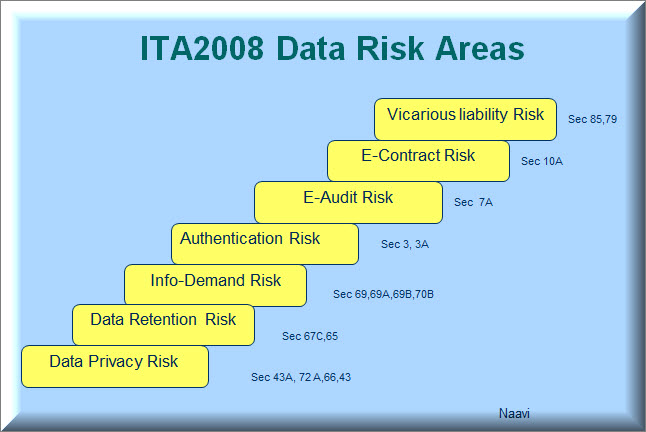

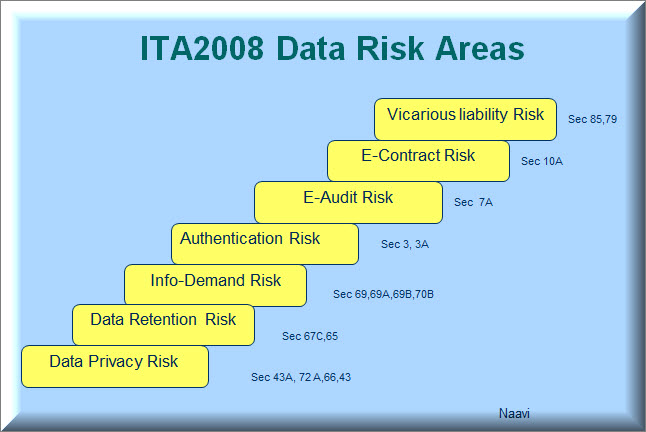

If we look at the India Information Security Framework created by Naavi, the following risks are identified in non compliance of ITA 2000.

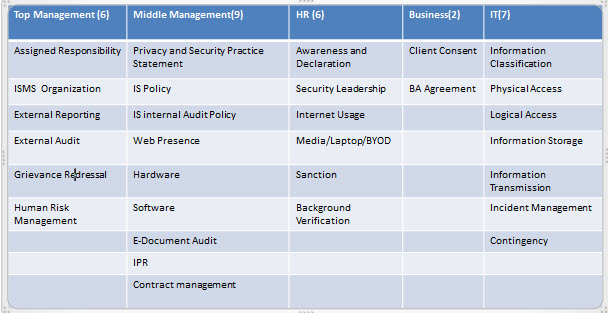

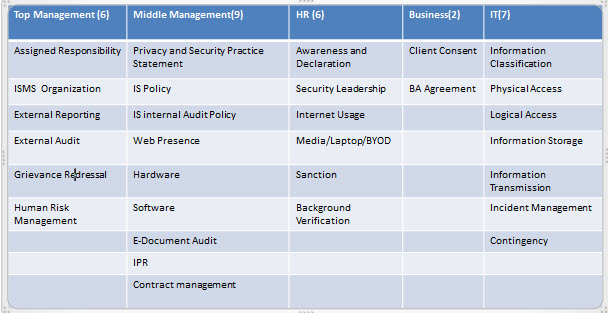

The corresponding compliance framework IISF shown below describes the compliance requirements in general.

The above compliance requirements are already integrated to the DPCSI (Data Protection Compliance Standard of India” and the DTS mechanism developed by Naavi/FDPPI.

If we carefully observe the Risk areas mentioned above, ITA 2000 goes much beyond Section 43A in imposing data protection without distinguishing between whether they are personal or non personal.

While Section 43A is restricted to Body Corporates (Which includes all non Government bodies) and imposes pre-emptive compliance measures in respect of Sensitive personal data as defined in ITA 2000, Section 43 applies where ever the value of data residing inside a computer resource is diminished. This is a pretty broad definition and covers all aspects of “Harm” that the data protection bill envisaged.

As regards compliance of Section 43A, even organizations other than Naavi, such as DSCI have come up with their own frameworks for compliance. Naavi has expanded it into a comprehensive IISF framework and also integrated the PDPB provisions as “Due diligence” elements in the DTS assessment.

In the recent days, CERT IN has shown a tendency to start invoking its powers to some extent and if they so desire, they can be more stringent than the DPAI under PDPB 2019.

In view of the above, organizations need to avoid complacency and continue their efforts on Data Protection.

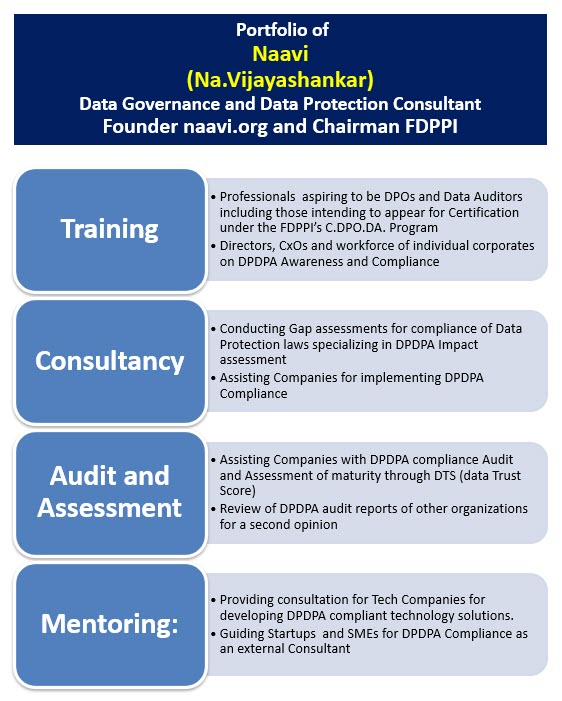

Naavi