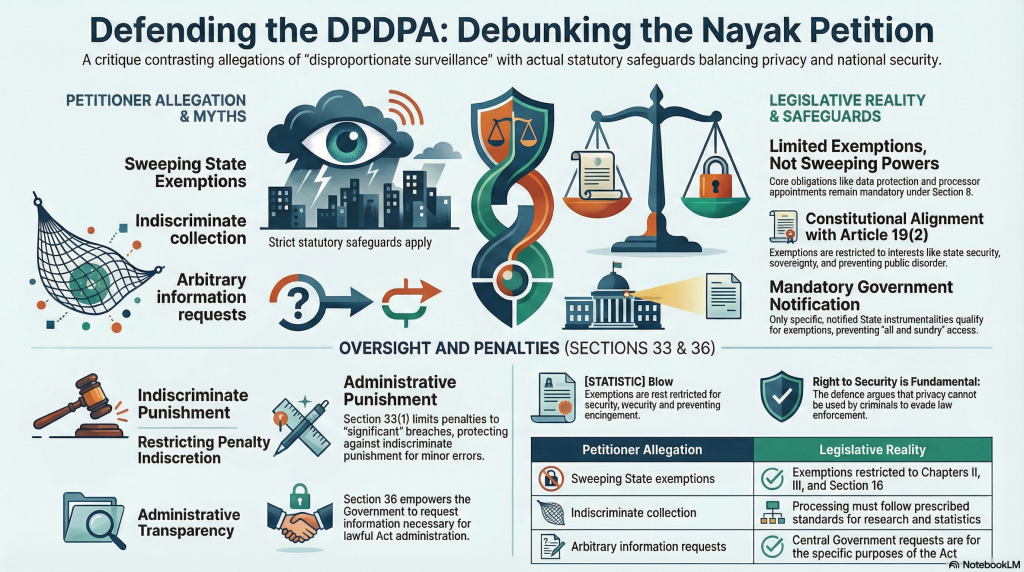

We have tried to point out inconsistencies in the petitions of the “Scrap-DPDPA Brigade” through many of our previous articles.

We have tried to point out inconsistencies in the petitions of the “Scrap-DPDPA Brigade” through many of our previous articles.

The net point we are making is

Objection Section 44(3) is not relevant since

a) Every PIO should not be forced to take a judicial view under DPDPA whether Privacy interests are involved or not in releasing an information

b) PIO may naturally opt to take the safety first option of rejecting release if prima facie personal information is involved so that the disgruntled applicant can invoke either the Grievance redressal mechanism under ITA 2000/DPDPA or RTI Act.

We have addressed some part of the objections related to exemptions under Section 17 which we shall explore further now.

DPDPA has to be considered as a law which is different from GDPR. Its approach to Personal Data Protection is different from that of GDPR. Similarly, DPDPA 2023 cannot be directly linked to the Puttaswamy Judgement on “Privacy is a Fundamental Right”. DPDPA 2023 is about personal data protection by organizations at the instance of the data principal. Protection of Privacy or being compliant to Privacy Principles under GDPR are incidental.

The petitioners have failed to look at DPDPA 2023 as an independent legislation and are trying to interpret it under different lens of either a Privacy Activist or a GDPR follower. These are giving raise to some disagreements. The Supreme Court has to appreciate this difference before giving any value to the arguments of the petitioners.

We shall try to address some of these issues here.

First of all, we need to take note of the following character of DPDPA 2023

- DPDPA 2023 has not segregated Personal Data into Sensitive Personal Data and Non Sensitive personal Data

- DPDPA 2023 has designated Data Controllers under GDPR as Data Fiduciaries providing them additional fiduciary responsibilities to take decisions in the interest of the Data Principals beyond the Consent.

- DPDPA 2023 has chosen “Consent” as the only legal basis for processing of personal data since “Right of Choice” of the data principal is paramount to protect his “Personal Data Protection Rights”.

- It is the Data Principal who decides why he wants his personal data to be processed in a particular manner. It could be to protect his privacy or it could be to protect his Security or it could be to protect any other Right of his choice.

- The cross border restrictions are based on “Types of Data” and “Types of Data Fiduciaries” and not “Adequacy or SCC”

- The exemptions are also defined on the basis of “The purpose of processing more than the class of Data Fiduciaries”.

These are fundamental differences in the approach of DPDPA to Personal Data protection and should be borne in mind when discussing whether DPDPA 2023 is constitutional or not.

We cannot judge DPDPA 2023 as unconstitutional by what it fails to do. We have to rather look at what it proposes to do and determine whether it violates any constitutional principles.

Arguing that DPDPA is not constitutional because it does not protect “Privacy” the way the petitioners think it should is fallacious.

Petitioners have raised objections specifically on Sections 17(1)(c), 17(2).

When we look at Section 17,we can observe that it is divided into five sub sections namely 17(1), 17(2), 17(3), 17(4) and 17(5).

Section 17(5)

Section 17(5) is a section empowering the Government to provide any exemption within the next 5 years. By the end of 5 years, Section 17 will crystallize. Till then Section 17 is malleable and can be tuned as required. Hence even if some of the provisions of the current Section 17 is not acceptable, there is a self correcting ability within the Act and there is no need to scrap DPDPA.

Section 17(3)

Section 17(3) is a section that empowers the Government to declare any data fiduciary (including start ups and perhaps even digital publications) to be exempted from the provisions of Section 5 (Notice before collection), Section 8(3) (Completeness, Accuracy and consistency), Section 8(7) (Erasure on withdrawal of consent, Completion of purpose), Sections 10(Obligations of a Significant Data Fiduciary) and Section 11 (Right to Access).

Exemption under Section 17(3) is by specific notification and should be justified with th criteria of Volume and Nature of personal data processed. This would be documented and be available for judicial scrutiny.

Section 17(4)

Exemption under Section 17(4) applies to State or instrumentalities of the State. It is applicable to Section 8(7) (Erasure on withdrawal of consent, Completion of purpose), 12(3) (Erasure of personal data as a Right). It is subject to a further condition that the processing does not involve making of a decision that affects the data principal and is not related to updation or correction of data.

Thus 17(3) and 17(4) and 17(5) does not result in any major harm to the data principal and is subject to judicial scrutiny when invoked.

This leaves Section 17(1) and 17(2) to discuss.

Section 17(1)

Section 17(1) is restricted to exemption of Chapter II (Obligations of a Data Fiduciary) other than 8(1) (Responsibility for a Data Processor) and 8(5) (Protection of Personal data). It is not restricted to Government bodies only but extends to Private sector also based on specific purposes such as

a) For enforcement of legal rights

b) Processing by Courts or other judicial entities

c) Prevention, detection, investigation or prosecution of any offence or contravention of any law

d) Data of foreigners processed in India

e)For processing during mergers and acquisitions after approval of Court

f) For processing by Financial Institutions after default

In these 6 subsections, the objections are being raised only on 17(1)(c) which is related to law enforcement duties. If the petitioners think Police should take prior consent for processing the personal data of a criminal or a suspected criminal, they are living in a world of fantasy. Their speculation that it can be used for wide spread surveillance of citizens is not based on any facts. It is a pure speculation and imaginary. If such a situation arises checks and Balances need to be set up by the Law enforcement agency itself.

While DPDPA does not exempt “Security” of data, other laws including Section 72 of ITA 2000, and Section 316 of Bharatiya Nyaya Samhita, include responsibilities that the law enforcement person should secure the data collected for prevention or detection of crime.

Hence there is a reasonable check and balance associated with the power and there is no reason to endanger the community by preventing the law enforcement from discharging their duty to secure the nation. The Right to Security of a Citizen is also a fundamental right and a sacred duty of the Government.

If the objections raised on Section 17(1)(c) is upheld it becomes a Right of a Criminal to hide under privacy excuses.

The same petitioners want Privacy not to be a constraint for release of information under RTI but have objections for collection of such information by the law enforcement for prevention of crimes. This is the typical Urban Naxalite mentality that tries to protect dishonest criminals at the expense of honest citizens.

Acceptance of the objection of the Rights of Law enforcement will weaken the security framework of the country and preserving it is well within the Article 19(2) of the Constitution.

Section 17(2)

Lastly we shall explore Section 17(2). This contains two subsections 17(2)(a) and 17(2)(b) both need to be discussed in depth.

Section 17(2)(a)

Section 17(2)(a) applies only to “Notified” instrumentalities of the State and can only be used

“In the interests of sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, maintenance of public order or preventing incitement to any cognizable offence relating to any of these,“

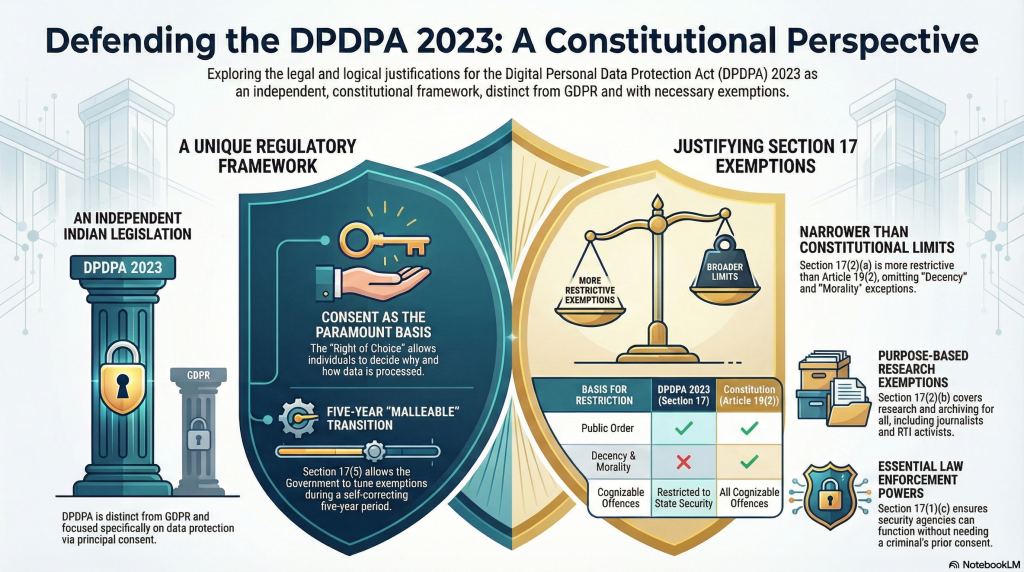

This sub section reflect the reasonable exceptions under Article 19(2) for Article 21 (from which right to privacy is derived).

It is interesting however to see that Article 19(2) states

Nothing … shall …prevent the State from making any law, in so far as such law imposes reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right conferred ….. in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with Foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence

Let us compare the two underlined portions.

| What DPDPA States | What Article 19(2) Peremits |

| maintenance of public order or preventing incitement to any cognizable offence relating to any of these |

public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence |

It is observed that DPDPA has curtailed the exemptions that were feasible under Article 19(2) substantially. For example, DPDPA has removed exception such as “Decency”, “Morality” and “Contempt of Court”. Even in respect of “Cognizable offences”, DPDPA restricts the exemptions only to such cognizable offences that relate to “interests of sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, maintenance of public order” and not to all cognizable offences.

Hence we cannot find any fault with the Government of having misused the provisions of Artile 19(2) and has shown extreme restraint in structuring Section 17(2)(a).

I donot see how the petitioners find this as giving “Sweeping powers of surveillance” etc except in their imagination.

Section 17(2)(b)

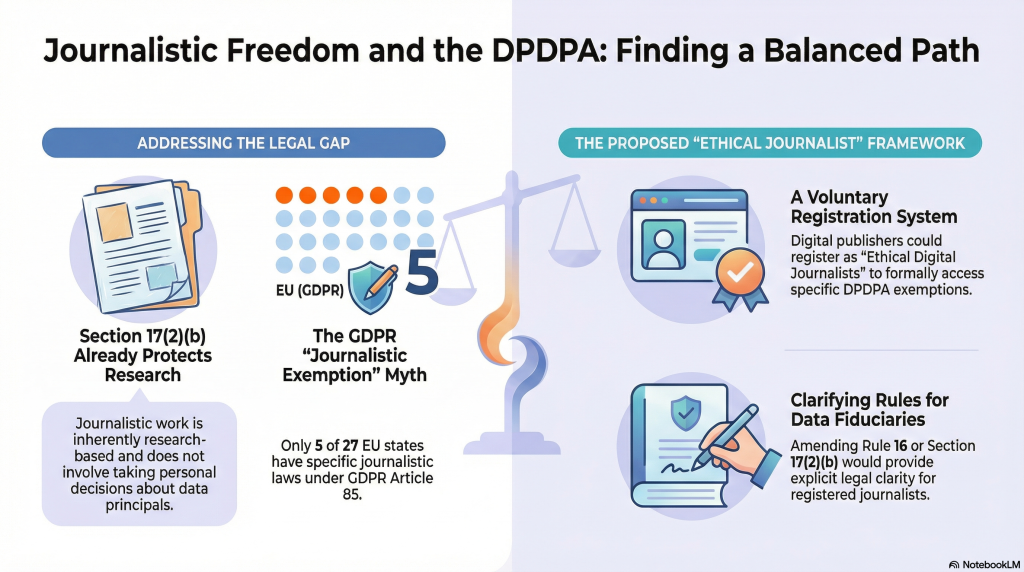

This sub section addresses the necessity for “Research”, “Archiving” and “Statistical Purposes” and has to be seen with the conditions attached to the exemption and the standards of security prescribed under the Rules 16(with Second schedule).

This also has relevance to the arguments of the Reporter’s Collective Trust that exemption has not been provided to the “Journalists” as a category of data fiduciaries.

Firstly we shall see the “Purpose” for which this exemption can be used. This subsection can be used for three aspects namely “Research”, “Archival” and “Statistical Analysis”. But it can be used only where there is no “Decision making” about the data principal involved. When a research is conducted, the output in the form of a report is generated. It can be used for general understanding of the market and not specifically to take a decision about the individual whose data is being processed.

As an example, when a hospital takes the diagnostic data about a patient, and uses it for diagnosis and delivery of its health services, the research done for the purpose is for taking a decision about the data principal. It is not exempt from DPDPA provisions.

The same data may be used to generate a research report about a decease and used for industry analysis not specifically for being used for the data principal. That research can even be done on de-identified or pseudonymized or anonymized data of patients.

Statistical analysis can also be done on anonymized information.

Such processing is exempted from the provisions of the Act.

The Rule 16 reiterates the purpose of archiving and also the need for security etc.

There does not seem to be any objection for such Health related research or Financial research where there is no decision making and data is used subject to the security standards prescribed.

Role of a Journalist and his Research

The petition of the Reporter’s Collective Trust strongly objects to the category of “Journalists” not being specifically mentioned in the Act. It ignores the fact that even Research for Medical or Financial evaluation is also not specifically mentioned. Use for research by any type of organization whether it is public or private is covered under Section 17(2)(b). It even covers research by Reporter’s Collective Trust itself. I hope they have no objection for it.

The case of RTI activist also comes under comparable objectives. An RTI activist may conduct a research involving personal data provided it is not required to be used for any decision making against the individual, including filing an objection for a benefit granted by the Government under a scheme or for alleging corruption against the official. If the RTI activist needs to do a research on how a Government scheme is functioning, he can request and work with pseudonymized information or even anonymized information. In such an instance the objections raised under Section 44(3) also become meaning less since the PIO can release data without the personal identity. I am sure that the Government can make arrangements to remove the identity in a set of data to be released subject to cost and time involved.

If a Journalist wants to use any information for a journalistic research, the Act does not bar him from claiming the exemption as long as he can justify that the requirement is for a “Research”. The special case of an “Investigative report” which later becomes a “Disputed defamation” exercise is to be handled as a “Risk for the Investigative journalist”. If he collects data on his own through research without specific consent or legal basis and uses it for developing a report which does not contain any identity of a person, then the report would be considered as not infringing privacy of any person and as long as the personally identified information collected for the research is held confidential and secure by the journalist, there should be no issue of non compliance of DPDPA and the fines.

It is true that GDPR may make a specific mention of “Journalist” for exemption purpose. At the same time GDPR also speaks of Churches for exemption. India has chosen not to specifically exempt either Journalists not doctors nor advocates nor chartered accountants nor temples, nor churches nor mosques, nor educational institutions nor madrassas, an exempted category as of now. The law has specified if the purpose is research, archival, statistical analysis, provision of benefits to the population etc then some exemptions may be available either under Section 17 or under legitimate use under Section 7.

Indian law is fair and does not discriminate different kinds of data fiduciaries for this purpose. It only tries to classify some data fiduciaries as “Significant Data Fiduciaries” and imposes additional obligations.

Just as journalists tomorrow objections can be raised by SMEs or Micro enterprises or One man Business entities why they are not provided exemptions etc. The demand by Reporter’s Collective is to introduce a “Discrimination” in the name of “Journalism” which is not warranted.

Further in the modern world of digital journalism, every individual who writes a blog or posts a Youtube video or a Tiktok reel, is a journalist. Why should a journalist registered with the Reporters’s Collective alone be provided a special status? The Intermediary guidelines under ITA 2000 does not spare an individual blogger from punishment if he violates a law. Hence the concept of “Who is a Journalist” in the digital media era has changed and there is no need to provide a special status to the journalists.

The days when Journalists were considered as the “Fourth Pillar of Democracy” is long lost. Today every journalist is either an employee of a journal or a contractual employee of some publication or George Sorros or a Political party. Hence there is absolutely no reason why “Journalists” should be considered as a special category of Data Fiduciaries and given some exemptions.

For example Naavi is himself a prolific writer and a journalist and Naavi.org itself is a publication. We have even submitted request for registration under the MeitY scheme of self regulation of digital media. However naavi.org may not have a registration with the Press Council or the Reporter’s collective and may not get invitations for Government events or IPL matches.

I therefore consider that the petition of Reporter’s collective claiming extra privileges under DPDPA is not relevant and must be dismissed.

Let us see if what we have expressed here reaches the ears of the Supreme Court or atleast the Meity or the Attorney General. Let us not allow the petitioners to use their selective presentations to mislead the Court.

In summary, I request the Supreme Court to judge DPDPA by what it does and not what it does not do but what petitioners wish it would do. Let DPDPA stand by its own Karma and not what any RTI activist or a journalist claiming to represent the public wishes.

Naavi

P.S: I would be happy to receive any comments… or even counter arguements.

Above picture is representative and has been created using Nanobanana AI tool

Above picture is representative and has been created using Nanobanana AI tool