We refer to our two earlier articles on the subject of “Data Governance Framework” and the new Expert Committee on Data Governance that has been announced.

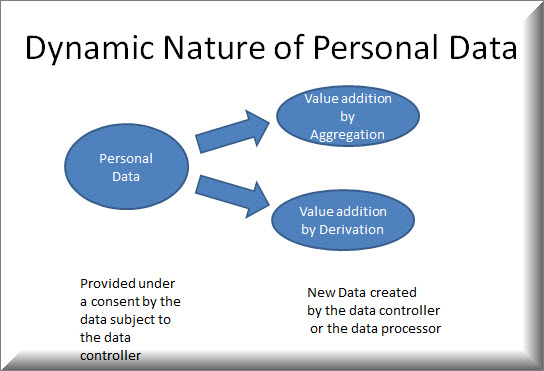

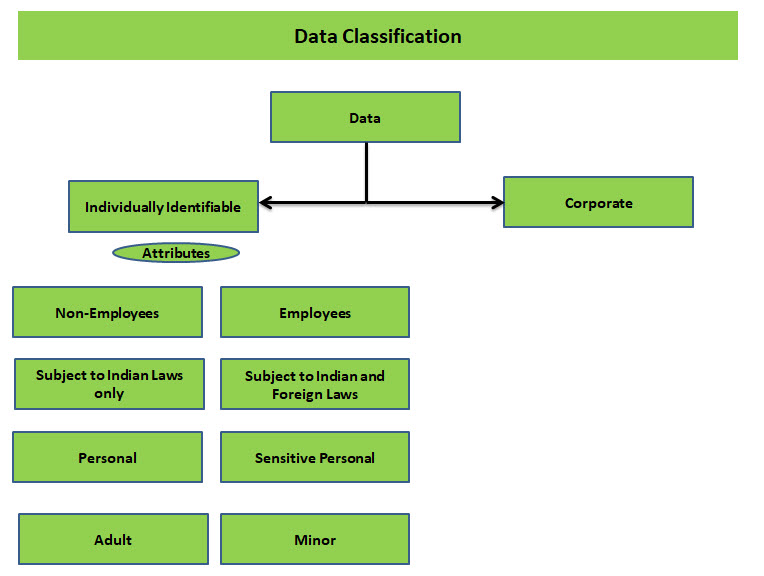

It was pointed out that the Srikrishna committee had spoken of the necessity of a new regulation for what Justice Srikrishna described as “Community Privacy”. This new “Right” of the “Community” was recognized because the “Identified Personal Data” of individuals to which the PDPA (Personal Data Protection Act) referred to, would when aggregated lead to “Identifiable Community Data”.

The notification of the committee however referred to a different term called “Non Personal Data”. Non Personal Data could be “Anonymized Data” since “Anonymized data” is any way out of scope of PDPA and not considered as “Personal Data” at all.

Non Personal data however includes corporate business data as well as the community data which Justice Srikrishna committee referred to. Presently such data is being secured under ITA 2000/8 and the “Prohibition of Re-identification” under PDPA. But neither of these two aspects cover the concept of “Community Privacy” which remains a term yet to be legally defined and covered under any law.

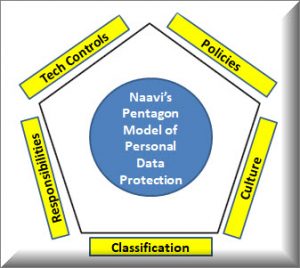

We pointed out in our articles that creating a regulatory framework for addressing the “Community Privacy” issues is a continuation of the PDPA work and is as complex as the personal data protection itself. We also pointed out that the “Data Governance Framework” as the industry perceives is today dictated by the Business requirements of an enterprise and the personal data protection requirements are super imposed on the Corporate Data Governance Framework as “Compliance Requirements”.

We pointed out that the notification refers to “Deliberation of Data Governance Framework” but refers to the Srikrishna committee in is preamble( Which concerned with Community privacy”), while the terms of reference made a reference to issues related “Non Personal Data”. In the context of the legislatory requirements envisaged by the Justice Srikrishna committee, it was also pointed out that the constitution of the committee did not reflect the requirements.

If however, the reference to Srikrishna committee is ignored and what this committee is to deliberate is only on “Big Data Processing”, then its constitution with people with IT industry experience is good enough. It would then be like the Committee on E Commerce which gave its own recommendations within the PDPA provisions. But the committee in its final report should not over step its expertise boundaries and recommend concessions to the Data Analytics industry which would be in conflict with PDPA, either by design or by error.

I am reminded of two other instances in the legislative history of Cyber Laws in India which presented similar issues and Naavi.org had reasons to raise its voice.

The first was the “Expert Committee” which was formed in 2005 to look into amendments to ITA 2000 following the Bazee.com issue which wanted an immunity to be given to Intermediaries from being held liable under Section 79 of ITA 2000.

Second was when the G Gopalakrishna Committee of RBI deliberating on the E Banking security guidelines was tried to be manipulated by some Bankers within the Committee to secure their interests by declaring OTP and 2F authentication as “Electronic Signature”.

On both these occasions, Naavi.org vehemently opposed the moves and finally the committees made changes to incorporate the views.

In the first instance, the 2005 amendments were replaced with the 2008 amendments by the standing committee of the Parliament headed by a Congress MP Mr Nikhil Kumar. (Refer here)

In the second instance, the GGWG committee itself dropped an entire proposed chapter on legal issues and reverted back to the Internet Banking guidelines of 2001. (Refer here for details)

We wish that the Kris Gopalakrishna committee will be responsive enough to understand the concern expressed by us that What Srikrishna Committee wanted is different from what the terms of reference to this committee indicate and it would not be proper for this committee to tread into the shoes of regulatory extension of PDPA, unless the committee consists of a strong judicially oriented person/s. Otherwise the committee may come up with recommendations which will meet opposition of Privacy activists.

What Kris Gopalakrishna says

In this context it is interesting to note what Mr Kris Gopalakrishna has said yesterday in an interview with ET.

His comments as indicated in the ET report are as follows and we shall comment on each of these as the “Views of the Chairperson of the proposed committee which may redefine Privacy laws in India”.

a) “the broad strokes of data regulations lie in trying to leverage the economic value of data for the benefit of the citizens, not just for corporations, and protecting them from the vulnerabilities inherent in the digital era.”

b) “India has a huge opportunity to leverage data in every aspect: data will be very important in providing credit, better banking services, healthcare, education, retail and ecommerce.”

c) “Everywhere, the efficiency can be improved, services levels enhanced. It is not just the companies benefitting, the individual also benefits,”

d) “Globally, companies are looking at anonymising data — stripping data sets of personal attributes of individuals and gleaning meaningful inferences from the data points.”

e) “The understanding of data privacy would go through a change once the boundaries around data were clearly drawn, dispelling concerns about disclosing identity”.

f) “Establishing policies around data, how industry must responsibly use your data and respect your privacy — today it’s not codified and hence the worry about disclosing your identity,”

g) “I think our concept of privacy will go through a change because we are voluntarily disclosing whom we are because we want some service”.

h) In the physical world, property rights have been clearly established. I think, over time, property rights will be clearly established in the online world.”

i) “Unfortunately or fortunately, data, compared to all the previous eras — agriculture, manufacturing and IT or digital — where the economic value lay in physical goods, knows no national boundaries. It can be transmitted without friction. How does a nation create value on the data of its citizens? How does a nation protect the data of its citizens? These are the questions everyone is grappling with”.

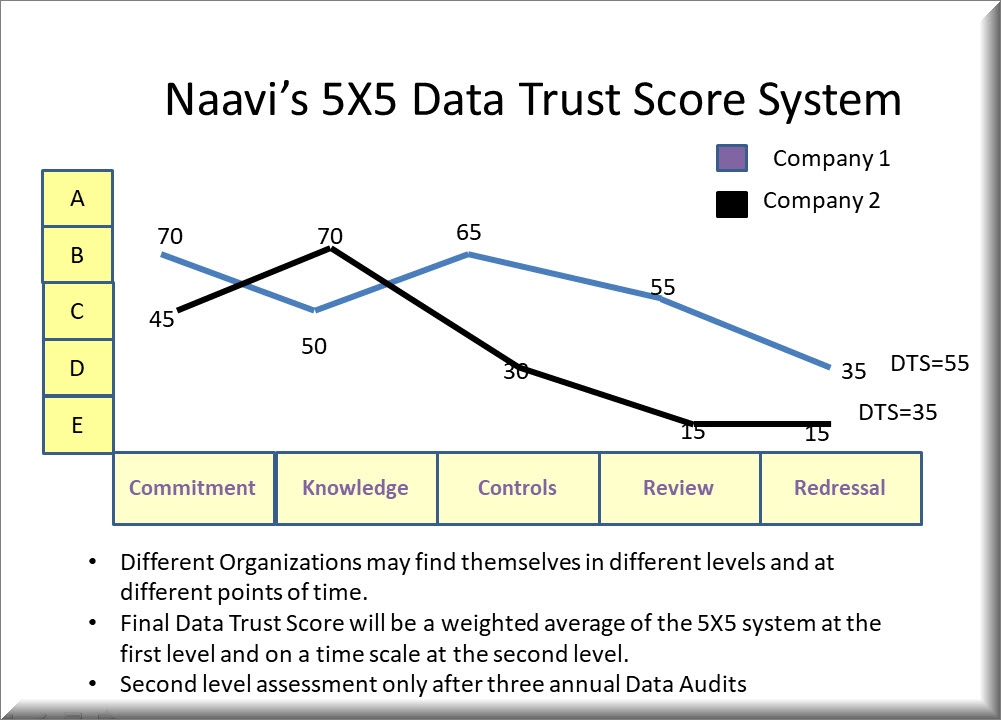

These indicate his present views and could get reflected in the final report of the committee also. It can be considered as what the Committee may view as its own interpretations of the terms of reference.

Hence we need to take this up for debate so that the Committee proceeds in the right direction.

My Comments on the above views will follow in the next article. Readers can also send their comments to Naavi.

Naavi