CIO Prime has featured Naavi as the most influential visionary leaders of the year. Reflecting on the past in the light of this article I recall

1) First book on Cyber Laws in India in 1999 before the law was passed.

2). Creation of www.naavi.org (initially as naavi.com) as a Cyber Law Portal

3) Introduction of first Virtual education through Cyber Law College

4) Introduction of Cyber Law Courses in KLE Law College, SDM Law College, JSS Law College, BMS Law College, St joseph Law College as well as NLSUI, NALSAR

5) Introduction of Cyber Law for Engineers at PESIT, Bangalore

6) Handling the Cyber Evidence Archival Center and presentation of India’s first Section 65B certificate in the case of State of Tamil nadu Vs Suhas Katti

7) Handling of S. Umashankar Vs ICICI Bank case through adjudication, Cyber Appellate Tribunal, TDSAT and Madras High Court through 14 years of litigation.

8) Formation of FDPPI

9) Creation of Certificate programs for Data Protection Professionals in 2019

10) Book on “Guardians of Privacy..”

11) Introduction of course on Data Protection at NALSAR

12) Introduction of Data Protection to management students in IIM Udaipur

13) Concept of Naavi’s Theory of Data

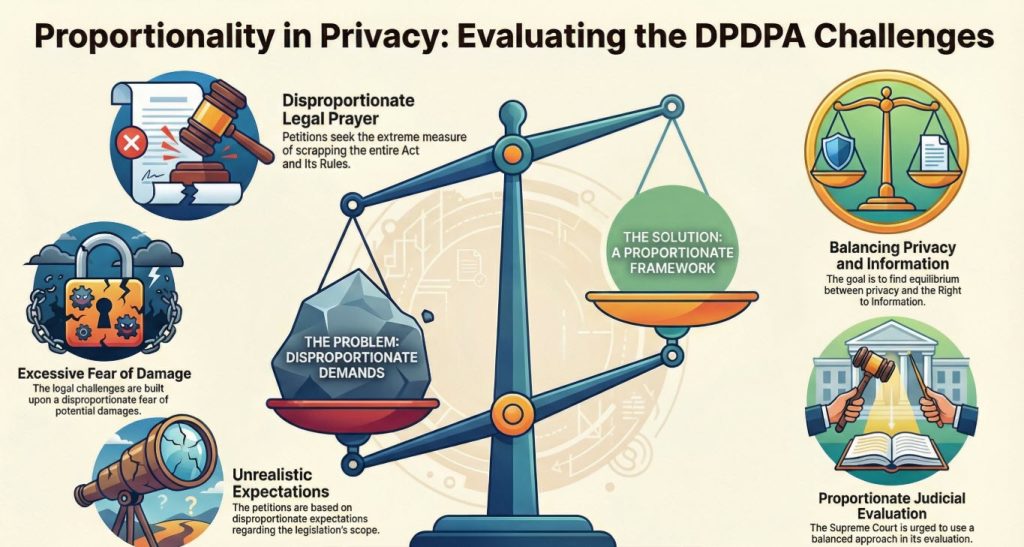

14) Introduction of DGPSI (Data Governance and Protection Standard of India) as a framework for compliance of DPDPA

15) Concept of Data Valuation Standard of India

16) Introduction of DGPSI-AI as a framework for AI regulation

17) Introduction of DGPSI-GDPR taking the Made in India framework to the global scene

18) Introduction of DGPSI-DP to push for voluntary DPDPA Compliance by Data Processors

19) Receipt of the Dena Bank award of public excellence

20) Receipt of the Life time achievement award for Cyber Jurisprudence

21) Receipt of the life time achievement award for Privacy.

There would be many more achievements that could have been missed in the above list.

Nothing gives me more satisfaction than creating DGPSI as a framework for Compliance which is blossoming into multiple dimensions such as DGPSI-AI, DGPSI-HR,DGPSI-DP, DGPSI-GDPR etc.

Hope the list expands further in the days to come.

There are two projects CEAC Drop Box and Online Dispute Resolution (ODR Global) which still hold huge promises yet to be realized. Hope these dreams come true in the coming year along with a major initiative in DPDPA which should be unveiled shortly.

Reminded of the words of Nehru duing our independence ..”Miles to go before I sleep, Miles to go before I sleep”..

Naavi