In debating the DPDPA implications arising out of employment contracts, one issue that comes forth is how the “GIG Workers” get represented in the DPDPA. In this connection we can refer to the The Karnataka Platform Based Gig Workers (Social Security and Welfare) Act, 2025, Act No. 72 of 2025 which has been effective from 30th May 2025

As per the Karnataka act, “Gig worker” means a person who performs work or participates in a work arrangement that results in a given rate of payment, based on terms and conditions laid down in such contract and includes all piece-rate work, and whose work is sourced through a platform, in the services specified in the Schedule;

(The Act is applicable only to platform based Gig workers and not others. Applicability for others who might apply for registration with the Board is not clear.)

Currently, Indian labour and employment laws recognize three main categories of employees: government employees, employees in government-controlled corporate bodies known as Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) and private sector employees who may be managerial staff or workmen. All these employees are ensured certain working conditions, such as minimum wages under The Minimum Wages Act, 1948, a set number of hours of work, compensation for termination, etc. Currently, gig workers lack the ‘employee’ status under Indian law, thereby resulting in several consequences, such as an inability to form unions to represent their interests, exploitative contacts, etc

The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 regulates engagement of contract labour in India, including work done through third-party contractors. There is scope for gig workers who work for platforms to be “contractors” under this law. This imposes obligations on employers to comply with the requirements under this law, including welfare and health obligations to be provided to employees such as the provision of canteens, first aid, etc

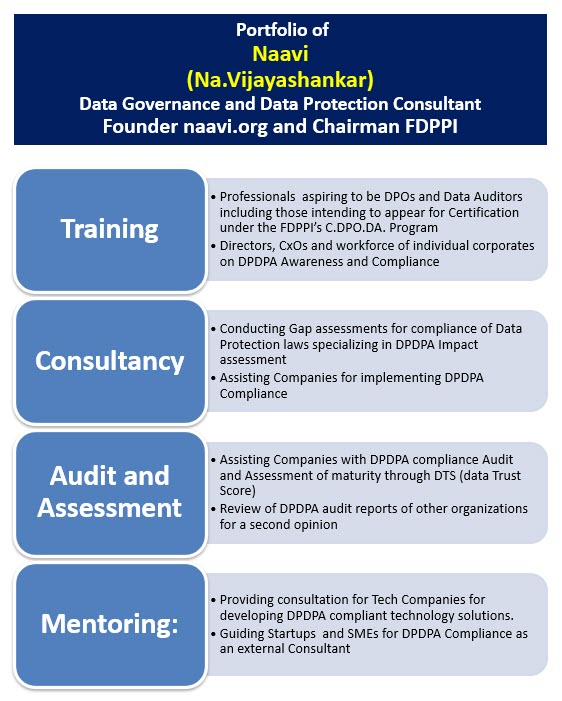

Under DGPSI we have been frequently mentioning that an “Individual” who works under a contract with another organization in a capacity other than “Employment” should be considered as a “Joint Data Fiduciary” or a “Data Processor” depending on the terms of the contract and whether it deals with personal data processing.

[Recently, there was a debate with an AI model on whether an individual can be a “Data Processor” under the DPDPA 2023, and I held the view that if an individual can be a data fiduciary under DPDPA, then he can also be a data processor. This was like the Arnab-Blue Machine debate and finally I decided to keep my view for the time being as the Jurisprudential view consistent with our approach to DGPSI.

The “Jurisprudential” view whether right or wrong is the prerogative of the human. An AI can only respond from the training data and is not capable of expressing the “Jurisprudential View”. The “Jurisprudential View” falls within the “Creative interpretation” which also introduces the “Unknown Risk” and hence not expected of an AI tool. This is another indication that AI as a tool can substitute lower level employee decisions which are routine in nature and not decisions which are not supported by past data. ]

Leaving this digression aside, let us dive deeper into the Karnataka Act which was aimed towards rapido, amazon kind of aggregators and a “Platform” defined as

… any arrangement providing a service through electronic means, at the request of a recipient of the service, involving the organization of work performed by individuals at a certain location in return for payment, and involving the use of automated monitoring and decision making systems or human decision making that relies on data.

To the extent this law tries to regulate “Cyber Space Activities”, we still consider that such laws made by State Governments are ultra-vires section 90 of Information Technology Act 2000, though even the central Government is not interested in pressing this nuance.

The main purpose of the Act is to provide “Social Security” for GIG workers with the constitution of a Welfare Board.

One of the obligations of the platform is to enter into “Fair Contract” with the Gig workers.

More importantly, the law states

“Section 13 (1) The aggregator or platform must inform the platform based gig worker, in simple language and in Kannada, English or any other language listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India known to the Gig worker, regarding the procedure to seek information in respect of the automated monitoring and decision making parameters employed by the aggregator or platform, which have an impact on their working conditions, including but not limited to fares,

earnings, customer feedback and allied information, as may be prescribed.

(2) The aggregator or platform shall take measures to prevent discrimination on the basis of religion, race, caste, gender, or place of birth or on the grounds of disability by the automated monitoring and decision making systems deployed by

them”.

While the platform is obliged to follow the law as mentioned in sec 13(2), it fails to recognize the right of choice of the consumer to designate the qualifications of a worker who provides the service. This needs to be debated.

This act is applicable to the following services.

1. Ride sharing services.

2. Food and grocery delivery services.

3. Logistics services.

4. e-Market place (both marketplace and inventory model) for wholesale/retail sale

of goods and/or services Business to Business /Business to Consumer (B2B/B2C).

5. Professional activity provider.

6. Healthcare.

7. Travel and hospitality.

8. Content and media services

When we discuss “Health Care” for GIG workers, we normally associate it with platforms such as “Practo” or “Nursing services” etc .

A point to discuss is whether a “Specialized Surgeon providing services in a hospital not as an employee but as a consultant” would also fall into the definition of a “Gig Worker”?

If so, then the “Right of Choice” of the consumer to restrict the choice of the service provider should also be recognized since it is a life critical decision.

If the principle of “Right of Choice to chose a service provider” is recognized for the medical profession, the next question is why it should not be applied to the food delivery like situation or a ride sharing service. Can the consumer restrict that the service should be provided only by a certain gender or religion etc without it being considered as “Discriminatory”?

We recall the debate in UP where the Government mandated that food stalls should display the owner details too enable the consumers to chose which stall to chose. Though this was opposed at that time for political reasons, in a neutral situation, this should be a “Consumer Choice”. If so, the platforms need to ask for such choice from the consumer and follow his “Permission” to use any specific category of service provider.

I am sure that this will be flagged as undesirable, but needs an impassioned debate . However the presence of this law corroborates the need to recognize three kinds of “Contractual Employees” in the DGPSI-HR framework namely

-

- An employee of organization A being placed to work in organization B under an organization to organization contract with a possible Personal Data Processing assignment.

- An employer B who accepts contractual employees from another organization A and assigns personal data processing work to them.

- A Contractual employee (GIG worker) of organization A being assigned to organization B for personal data processing assignments.

The DGPSI-HR framework suggests appropriate policies and back to back contracts to ensure that the responsibilities of a Data Fiduciary are properly managed in such situations.

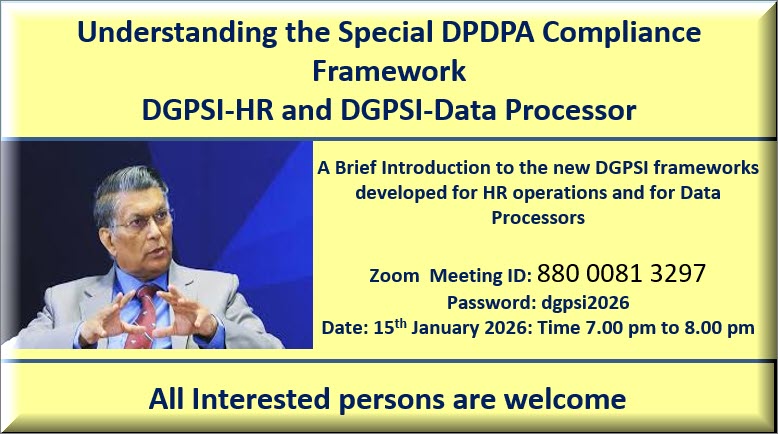

Let us debate this today in the open house discussion on DGPSI-HR. Be there if you are interested.

Naavi