Naavi.org had started a discussion on Neuro Rights during the Indian Data Protection Summit 2022 ( IDPS 2022) where Professor Raael Yuste, a professor and Neuro Scientist from Columbia University had presented his views through a virtual talk.

(Other articles on Neurorights can be found here)

At that time, Chile was the only country which had recognized Neuro Rights through a Constitutional wmendment. Subsequently, in September 2024, Colarado and then in October 2024, California signed a law recognizing Neuro Rights as “Sensitive Personal Right” under the Privacy law.

Now Brazil, Spain and Mexico have also adopted Neuro Rights Protection through appropriate constituional amendments. (Refer here)

The five principal Neuro Rights recognized by the NeuroRights Foundation are

-

Right to Mental Privacy This ensures that data obtained from measuring neural activity (brain data) cannot be sold, transferred, or used without the individual’s explicit consent. It aims to keep thoughts and brain states private.

-

Right to Personal Identity This protects the “self” from being altered by external technologies. It ensures that neurotechnology (like brain-computer interfaces) does not blur the line between a person’s own consciousness and the output of a machine.

-

Right to Free Will This right ensures that individuals maintain control over their own decision-making processes. It aims to prevent external “neuro-manipulation” where a technology could influence a person’s choices without their knowledge.

-

Right to Equitable Access to Mental Augmentation To prevent a new type of “neuro-divide,” this right advocates for fair and equal access to cognitive-enhancement technologies across society, ensuring they aren’t reserved only for a wealthy elite.

-

Right to Protection from Algorithmic Bias This ensures that the algorithms used in neurotechnology are designed without bias. It protects individuals from being discriminated against based on data extracted from their brain activity.

The harms normally recognized in the context of technolofical intrusions to human brain are

- Neural Privacy Breaches

- Unauthorized brain data collection

- Neural data theft

- Cognitive surveillance

- Cognitive Liberty Infringement

- Forced neural modification

- Involuntary thought monitoring

- Cognitive manipulation

- Mental Integrity Violations

- Non-consensual neuromodulation

- Psychological manipulation through neurotechnology

- Neural identity interference

- Neuro-Discrimination

- Employment discrimination based on neural data

- Insurance discrimination

- Social scoring based on brain metrics

Each type of violation presents unique challenges and requires specific protective measures and legal frameworks.

The Parliament of Latin American counries (Parlantino) had introduced a “Model Law” with 13 articles (Refer here)

Presently it has been reported that Canada has also taken a decision to recognize Neuro Data as “Sensitive Personal Information” under the PIPEDA.

While discussions continue on how Neuro Rights Protection can be achieved, the simplest approach has been to use the existing privacy laws by declaring neuro data as “Sensitive Data”. In India, under DPDPA, this can be done by declaring an organization processing neural data as a “Significatn Data Fiducairy”.

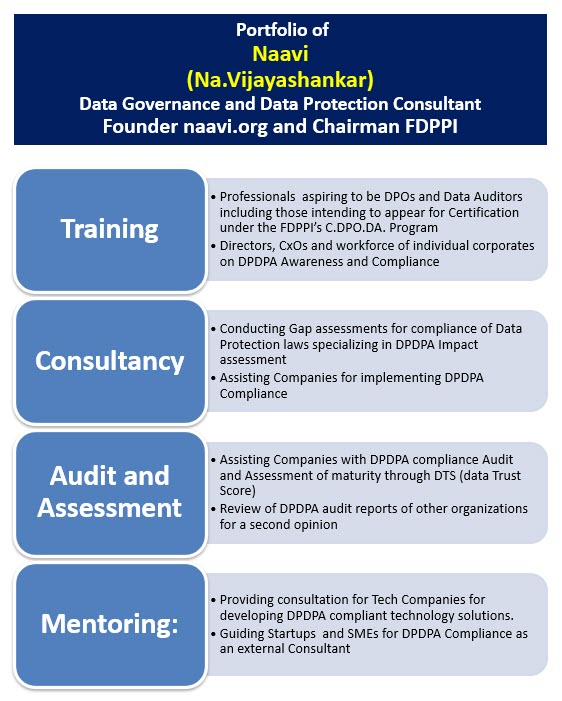

I invite further discussions on this aspect. In the mean time, DGPSI will use the criteria that “Processing of Neural Data” imposes “Significant risks” and hence the data fiduciary should be considered as a Significatn Data Fiduciary.

It would be interesting for readers to observe that Naavi.org had suggested a “CyBorg regulation” where consensual intervention of human brain was discussed. What a broader Neuro Rights law may mandate is the regulation through a consent mechanism under the DPDPA itself.

Open for debate.

Naavi