Book Review: Taming the Twin Challenges of DPDPA and AI

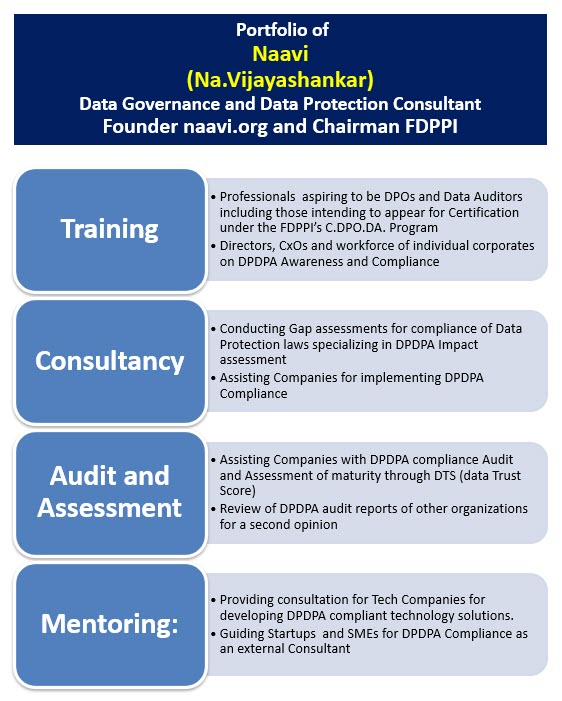

Overview and Context: Taming the Twin Challenges of DPDPA and AI with DGPSI-AI is the latest work by Vijayashankar Na (Naavi), building on his earlier DPDPA compliance handbooks. Published in August 2025, it addresses the twin challenges of India’s new Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDPA) and the rise of AI. The book is framed as an extension of Naavi’s DGPSI (Digital Governance and Protection System of India) compliance framework, introducing a DGPSI-AI module for AI-driven data processing. The author situates the work for data fiduciaries (“DPDPA deployers”) facing the DPDPA’s steep penalties (up to ₹250 crore) and “AI-fuelled” risks. In tone and organization it is thorough: the Preface and Introduction review DPDPA basics and AI trends, followed by chapters on global AI governance principles (EU, OECD, UNESCO), comparative regulatory approaches (US states, Australia), and then the DGPSI-AI framework itself. While Naavi acknowledges the complexity of AI for lay readers, his goal is clear: to equip Indian compliance professionals and technologists with practical guidelines for the AI era.

Overview and Context: Taming the Twin Challenges of DPDPA and AI with DGPSI-AI is the latest work by Vijayashankar Na (Naavi), building on his earlier DPDPA compliance handbooks. Published in August 2025, it addresses the twin challenges of India’s new Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDPA) and the rise of AI. The book is framed as an extension of Naavi’s DGPSI (Digital Governance and Protection System of India) compliance framework, introducing a DGPSI-AI module for AI-driven data processing. The author situates the work for data fiduciaries (“DPDPA deployers”) facing the DPDPA’s steep penalties (up to ₹250 crore) and “AI-fuelled” risks. In tone and organization it is thorough: the Preface and Introduction review DPDPA basics and AI trends, followed by chapters on global AI governance principles (EU, OECD, UNESCO), comparative regulatory approaches (US states, Australia), and then the DGPSI-AI framework itself. While Naavi acknowledges the complexity of AI for lay readers, his goal is clear: to equip Indian compliance professionals and technologists with practical guidelines for the AI era.

Clarity of AI Concepts

The book devotes an entire chapter to demystifying AI for non-technical readers. Naavi explains key terms (algorithms, models, generative AI, agentic AI) in accessible language. For example, he describes generative AI (e.g. GPT) as models trained on large datasets to predict and generate text, and agentic AI as systems that “plan how to proceed with a task” and adapt their outputs dynamically. This pragmatic framing helps the intended audience (lawyers, compliance officers) understand novel terms. The writing is generally clear: e.g., the book notes that most users became aware of AI through ChatGPT-style tools, and it uses everyday analogies (using Windows or Word without knowing internals) to justify a non-technical approach. In this way it succeeds in making AI concepts understandable. However, the text sometimes oversimplifies or blurs technical distinctions. The author even admits that purists may find some terms used interchangeably (e.g. “algorithm vs model”). Similarly, speculative ideas (such as Naavi’s own “hypnotism of AI” theory) are introduced without deep technical backing. While this keeps the narrative flowing for general readers, technically minded readers might crave more rigor. Overall, the discussion of AI is approachable and fairly accurate: it correctly identifies trends like multi-modal generative AI, integration into browsers (e.g. Google Gemini, Edge Copilot), and the spectrum of AI systems (from narrow AI to hypothetical “Theory of Mind” agents). The inclusion of Agentic AI is particularly innovative: Naavi defines it as a goal-driven AI with its own planning loop, echoing industry descriptions of agentic systems as autonomous, goal-directed AI. This foresight – addressing agentic AI before many mainstream works – is a strength in making the book future-facing.

Analysis of DPDPA and DGPSI Context

Legally, the book is deeply rooted in India’s DPDPA framework. It repeatedly emphasizes the novel data fiduciary concept (absent in GDPR) whereby organizations owe a trustee-like duty to individuals. The author correctly notes that DPDPA’s core purpose is to protect the fundamental right to privacy while allowing lawful data processing, and he cites this as a guiding principle (mirroring the Act’s long title). The text accurately reflects DPDPA obligations: for instance, it stresses that any AI system handling personal data invokes fiduciary duties and may require explicit consent or legal basis under the Act. Naavi also highlights the Act’s severe penalty regime (up to ₹250 crore for breaches), underscoring the high stakes. The book’s discussion of fiduciary duty is sophisticated: it observes that a data fiduciary “has to follow an ethical framework” beyond the statute’s words. This aligns with legal commentary that DPDPA imposes broad accountability on controllers (data fiduciaries).

Practically, the book guides readers through DPDPA compliance steps. Chapter 5 details risk assessment for AI deployments: Naavi insists that any deployment of “AI-driven software” by a fiduciary must start with a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA). This reflects DPDPA Section 33’s DPIA requirement (analogous to GDPR’s DPIA). He also explains that under India’s Information Technology Act, 2000 an AI output is legally attributed to its human “originator”, so companies cannot blame the AI itself. These legal explanations are mostly accurate and firmly tied to Indian law (e.g. citing ITA §11 and §85). In sum, the book treats DPDPA context with confidence and detail, though it sometimes reads more like an advocacy piece for DGPSI than an impartial analysis. For example, the text assumes DGPSI (and DGPSI-AI) are the “perfect prescription” and often interprets DPDPA provisions through that lens. But as a compliance roadmap it does cover the essentials: fiduciary duty, consent renewal for legacy data, DPIAs, data audits and DPO roles are all emphasized.

The DGPSI-AI Framework

The center piece of the book is the DGPSI-AI framework, Naavi’s proposal for AI governance under DPDPA. It is explicitly designed as a “concise” extension to the existing DGPSI system: just six principles and nine implementation specifications (MIS) in total. This economy is intentional (“not to make compliance a burden”) and is a pragmatic strength. The six core principles (summarized as “UAE‑RSE” – Unknown risk, Accountability, Explainability, Responsibility, Security, Ethics) are spelled out with concrete measures. For example, under the Unknown Risk principle, Naavi argues that any autonomous AI should be treated by default as high-risk, automatically classifying the deployer as a “Significant Data Fiduciary” requiring DPIAs, a DPO, and audits. This is a bold stance: it essentially presumes the worst of AI’s unpredictability. Likewise, Accountability requires embedding a developer’s digital signature in the AI’s code and naming a specific human “AI Handler” for each system. These prescriptions go beyond what most laws demand; they are innovative and enforceable (in theory) within contracts. The Explainability principle mandates that data fiduciaries be able to “provide clear and accessible reasons” for AI outputs, paralleling emerging regulatory calls for transparency. The book sensibly notes that if a deployer cannot explain an AI, liability may shift to the developer as a joint fiduciary. Under Responsibility, AI must demonstrably benefit data principals (individuals) and not just the company – requiring an “AI use justification” document showing a cost–benefit case. Security covers not only hacking risks but also AI-specific harms (e.g. “dark patterns” or “neurological manipulation”), recommending robust testing, liability clauses and even insurance against AI-caused harm. Finally, Ethics goes “beyond the law,” urging post-market monitoring (like the EU AI Act) and concepts like “data fading” (re-consent after each AI session).

In these six principles, the book demonstrates real depth. It does an excellent job mapping international ideas to India: e.g., it explicitly ties its “Responsibility” principle to OECD and UNESCO values, and it notes alignment with DPDPA’s own “fiduciary” ethos. The implementation specifications (not shown above) translate these principles into checklist items for deployers (and even developers). The approach is thorough and structured, and the decision to keep the framework tight (6 principles, 9 MIS) is a practical virtue. By focusing on compliance culture rather than hundreds of controls, the author aims to make adoption feasible.

Contributions to AI Governance and Compliance

This book makes a distinctive contribution to AI governance literature by centering India’s regulatory scene. Few existing works address AI under India’s data protection law; most global frameworks focus on EU, US or OECD models. Here, Naavi synthesizes global standards (OECD AI principles, UNESCO ethics, EU AI Act, ISO 42001, NIST RMF) and filters them through India’s lens. The result is a home-grown, India-specific prescription for AI compliance. The DGPSI-AI principles clearly mirror international best practices (e.g. explainability, accountability) while anchoring them in DPDPA duties. For compliance officers and legal teams in India, the framework offers a tangible roadmap: mandates to document training processes, conduct AI risk assessments, maintain kill-switches, and so on. For example, Naavi’s recommended Data Protection Impact Assessment for any “AI driven” process will resonate with practitioners already aware of DPIAs in the EU context.

In terms of risk mitigation, the book is forward-looking. It anticipates that data fiduciaries will increasingly use AI and that regulators will demand oversight. By recommending things like embedding code signatures and third-party audits, it pre-empts regulatory scrutiny. Its treatment of Agentic AI (Chapter 8) is also novel: Naavi correctly identifies that goal-driven AI agents pose additional risks at the planning level, and he advises a separate risk analysis and possibly a second DPIA for such systems. This shows innovation, as few compliance guides yet address multi-agent systems. Finally, the inclusion of guidance for AI developers (Chapter 9) is a valuable extension: although DGPSI-AI mainly targets deployers, Naavi provides a vendor questionnaire and draft MIS for AI suppliers (e.g. requiring explainability docs, kill switches). This hints at eventual alignment with standards like ISO/IEC 42001 (AI management) or NIST’s AI RMF. In short, the book’s contribution lies in melding AI governance with India’s data protection law in a structured way. It is unlikely that an AI developer or legal advisor working under India’s DPDPA would be fully prepared without considering such guidelines.

Strengths

-

Accessible Explanations: The book excels at clear, jargon-light explanations of complex AI ideas. It takes care to define terms (generative AI, agentic AI, narrow vs general AI) in plain language, making it readable for legal and compliance professionals.

-

Contextual Alignment: Naavi grounds every principle in Indian law and culture. For example, he links DPDPA’s fiduciary concept to traditional notions of trustee duty, and aligns “Responsibility” with OECD and UNESCO values. This ensures relevance to Indian readers.

-

Practical Guidance: The framework is deliberately concise (six principles, nine specifications) to avoid overwhelming users. It offers concrete tools: checklists, sample clauses (e.g. kill-switch clauses for contracts), and forms of DPIA. This hands-on focus is a major plus.

-

Innovative Coverage: Few works discuss agentic AI in a governance context, but this book does. It defines agentic AI behavior and stresses its higher risk, recommending separate oversight. Similarly, requiring “AI use justification documents” and insurance against AI harm shows creative thinking.

-

Holistic View: By surveying global standards (OECD, UNESCO, EU AI Act) and then distilling them into DGPSI-AI, the book situates India’s needs in the broader world. Its comparison of US state laws (California, Colorado) and Australia provides useful perspective on diverse approaches.

Critiques and Recommendations

-

Terminology Consistency: As the author himself notes, some technical terms are used loosely. For instance, “algorithm” vs “model” vs “AI platform” sometimes blur. Future editions could include a glossary or more precise definitions to avoid ambiguity.

-

Assumptions on AI Risk: The “Unknown Risk” principle assumes AI always behaves unpredictably and catastrophically. While caution is prudent, this might overstate the case for more deterministic AI (e.g. rule-based systems). A more nuanced risk taxonomy could prevent overclassifying every AI as “significant risk.”

-

Regulatory Speculation: Some content is lighthearted or speculative (e.g. a fictional “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” in the US chapter). While illustrative, such satire should be clearly marked or toned down in a formal review context. Future editions might stick to actual laws or clearly label hypothetical scenarios.

-

Emerging Standards Coverage: The book rightly cites ISO/IEC 42001 and the EU AI Act, but could expand on newer frameworks. For example, the NIST AI Risk Management Framework (released Jan 2023) is a major voluntary guideline for AI risk. Mentioning such standards (and perhaps IEEE ethics guidelines) would help readers connect DGPSI-AI to global practice.

-

Technical Depth vs. Accessibility: The trade-off between technical precision and readability is evident. Topics like model training, neural net vulnerabilities, or differential privacy receive little detail, which is fine for non-experts but may disappoint developers. Including appendices or references for deeper technical readers could improve balance.

-

Practical Examples: The book is largely conceptual. It would benefit from concrete case studies or examples of organizations applying DGPSI-AI. Scenarios showing how a company conducts an AI DPIA or negotiates liability clauses with a vendor would enhance the practical guidance.

Expert Verdict

Taming the twin challenges of DPDPA and AI is a pioneering and timely resource for India’s emerging techno-legal landscape. Its formal tone and structured approach make it suitable for web publication and professional readership. Despite minor stylistic quibbles, the book’s depth of analysis on DPDPA obligations and AI governance is impressive. For AI developers and vendors, it provides valuable insight into the compliance expectations of Indian clients (e.g. explainability documentation, kill switches). For compliance professionals and corporate counsel, it offers a clear roadmap to integrate AI tools under India’s data protection regime. And for legal stakeholders and regulators, it suggests a concrete “best practice” framework (DGPSI-AI) that anticipates both legislative intent and technological evolution. In an environment where India’s DPDPA rules and global AI regulations (EU AI Act, NIST RMF) are still unfolding, Naavi’s book charts a proactive course. It should be considered essential reading for anyone building or deploying AI systems in India, or advising organizations on data protection. With the suggested refinements, future editions could make this guide even stronger, but even now it stands as a comprehensive contribution to the field.

18th August 2025

ChatGPT