Anonymization is an important aspect of Data Protection in India. It segregates Data into two categories namely Personal Data for which the proposed PDPA-India will be applicable as per PDPB 2019 and Non Personal Data which is outside this regulation. According to PDPB 2019 the DPA (Data Protection Authority) when formed will issue the guideline for a standard of anonymization that would be acceptable under law.

It is understood that no technology is perfect and even the strongest of anonymization can be broken by hackers just as Encryption can be broken. Hacking of such nature can be made punishable but as long as hackers exist, it cannot be prevented.

Some hackers would not like themselves to be called hackers and they call themselves as “Security Researchers”. As long as their intention is to find out security vulnerabilities and they work for an organization under authority to find bugs in its processes they deserve to be called security researchers or white hackers. But the moment they turnover their findings to the dark web or use it for extortion, they become black hackers.

The standard prescribed by law can only introduce a reasonable limit for an organization to render an identified personal data to anonymized personal data. If the standard is set too high, it will be disproportional to the business needs. If it is set too low, it would not suffice.

Hence the DPA will have a task to ensure that a right level of difficulty is set for hackers to determine what level of technology is sufficient to call a personal data as anonymized.

ICO-UK has now come up with a guidance note on this topic which is a good starting point to understand how anonymization is interpreted in UK and how it is distinguished from De-Identification and Pseudnymization.

A copy of the guidance note is available here

Some key points in the guideline are as follows:

Anonymisation is the process of turning personal data into anonymous information so that an individual is not (or is no longer) identifiable.

Data protection law does not apply to truly anonymous information.

Pseudonymisation is a type of processing designed to reduce data protection risk, but not eliminate it. You should think of it as a security and risk mitigation measure, not as an anonymisation technique by itself.

It must be noted that

Anonymisation is the process of turning personal data into anonymous information so that an individual is not (or is no longer) identifiable.

Data protection law does not apply to truly anonymous information.

Pseudonymisation is a type of processing designed to reduce data protection risk, but not eliminate it. You should think of it as a security and risk mitigation measure, not as an anonymisation technique by itself.

It must be noted that Pseudonymization is similar to De-Identification in effect. In de identification, all identifiers are removed as a set and substituted with one proxy ID. In Pseudonymization, each identifier is replaced with a pseudo identifier.

Both de-identified and pseudonymized personal data may be re-identified by some body who has the mapping information. In anonymization, the mapping information is irretrievably destroyed so that even the person who anonymized it in the first place is not capable of identifying it without resorting to efforts which are not considered normal.

Unauthorized re-identification of de-identified/pseudonymized information as well as anonymized information is a punishable office under UK-GDPR as much as it is so in Indian PDPA.(proposed).

It is recognized that in some instances effective anonymization may not be possible due to the nature or context of the data, or the purpose(s) for which it is collected or used.

More guidelines are expected to be announced by ICO in due course as additional chapters to this guideline and may be a good document to keep track.

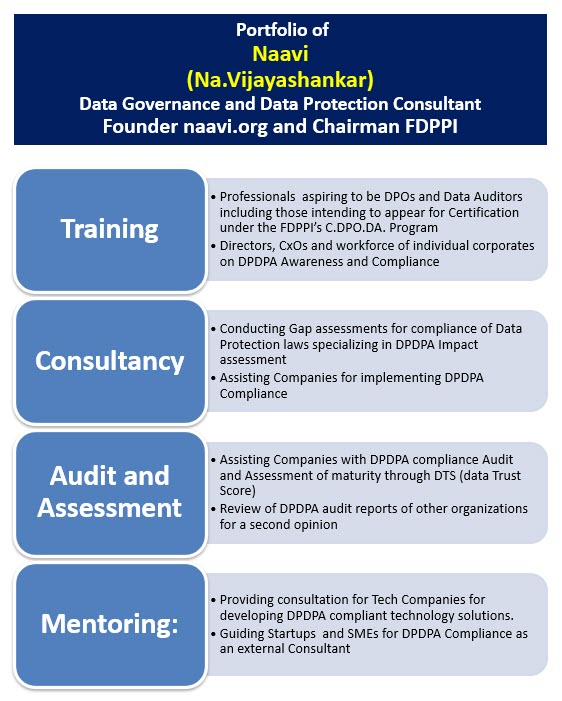

Naavi